October

2005

Featured

Artist: Ideas in Pictures

The Satya Interview with

Colin Matthes

By Roshni Koshy

|

|

Animals and Workers

Installation

|

|

Jefferson, WI |

A few months ago, upon leaving

the Taking Action for Animals conference, a man condescendingly asked

me, “Besides animals what do you

care about?” to which I responded, “My friends, my family,

and generally all people and how our actions affect all living beings.” The

guy smirked as if to say “good answer,” but still, I wish

I had also given him an issue of Colin Matthes’ zine (an independently

published magazine) Ideas in Pictures.

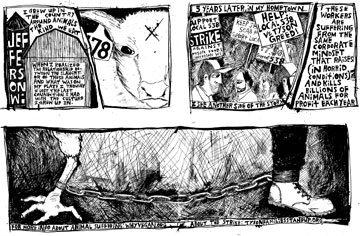

In the Wisconsin-based zine series, Ideas in Pictures, Matthes writes and graphically

illustrates the effects of factory farming not only on farm animals, but also

on the workers and the family farms in his hometown of Jefferson, Wisconsin.

This zine series serves as a supplement to each of Colin’s art exhibits,

which bring to life the struggles of both the human and nonhuman animals caught

up in the cycle of meat and dairy production. As a drawing and illustration professor

who grew up in a rural farming town, Colin’s work is an extension of his

own need to explore, connect, and actively participate in the world just outside

his front door.

Can you talk a bit about your zine series, Ideas in Pictures?

Growing up and being involved in punk I always had zines around me. [Later on],

I started making zines as a reaction to feeling unsatisfied with art shows. People

would interact with the art work, but once they left, that was kind of it. I

wanted to make a zine so that people could walk away with information on what

they just saw. I try to ask questions with my art work but I also try to provide

a more in-depth way to think about it, not necessarily concrete answers.

What was your life like growing up in rural Wisconsin?

Well I grew up in Jefferson—a small town in the country—where I was

surrounded by farms in every direction. My dad was an electrician and my mom

raised me and took care of the old farm house we lived in. The house was about

five miles from the nearest town, and that’s where I went to school. The

town was also a factory community. In fact, the second largest employer was a

meat processing plant. I’ve been around farms and factories pretty much

all my life. I didn’t think too much about it until I was away at college

and I got some pamphlets on the meat industry and veganism. Everything started

to click after that.

Which brings us to your Veal Crate exhibit and its corresponding zine

titled #18: A Leftover from the Dairy Industry. For this project you decide to

take

footage of a lovely calf “affectionately” named #18. Tell us about

this project.

Zine #18: A Leftover from the Dairy Industry documents a calf [living] on a family

farm. I wanted to stay away from the shock and gore aspect we see in so many

animal rights videos. It was important for me to capture the innocence of a calf—the

essence of the calf. I also wanted to explore the relationship between a factory

farm with veal crates and this calf on the family farm.

So [in the exhibit], I played the video of the calf inside an authentic veal

crate. On the outside you could see there was a video playing and that enticed

people to actually go inside the crate. I experimented with confusing the perspective

between family farms and factory farms by encouraging the viewer to enter a space

reserved for a factory farm animal, bringing another layer to the relationship

between factory and family farming.

In zine #3 titled Animals and Workers you state, “When I used to think

about the victims of the meat and dairy industry I would be thinking of the animals.

As time passed I widened my definition of meat industry casualties.” What

does this mean to you?

When I think of myself as being a vegan animal rights activist, I don’t

think animal rights should be isolated from everything else I do—from the

rest of the world. I think it’s all becoming increasingly more linked to

human rights. A lot of times the workers’ and the animals’ situations

can be more related than opposing. Family farmers in this country are going through

some really tough times. Where I’m from, in effort to keep a farm that

has been in their families for generations, a lot of farmers have to sell their

homes and live in trailers. The conditions are getting worse. So something like

exploiting animals is not even on their radar.

When you worry about making ends meet, and you see the quality of your life dwindling

right before your eyes, it’s that much harder to take into consideration

the lives animals.

A lot of times you grow up and that’s all you know—it’s not

like your environment has a lot of opportunities for you. You can take over the

family farm, work in the local factory, or you can be broke! Unless you go away

to college there’s not a whole bunch of different [options] available to

you. A lot of times, workers aren’t choosing to work in slaughterhouses

or factories—it’s not their ideal life. They’re really just

another part of the systemic problem of factory farming. It’s easy to judge

these workers, especially when videos show them doing horrible things to animals,

but in that environment there’s going to be a high level of cruelty based

on the condition. I mean, it’s just like the prison system—being

in that environment, you might not come out the same.

So why are people taking these jobs that call for such horrible working conditions?

A lot of these places, especially slaughterhouses, are moving into more rural

areas and becoming one of the only opportunities for work. Recently the targeting

has been geared to illegal immigrants and minority workers. It’s one of

the few occupations where you’re going to be able to make a little money.

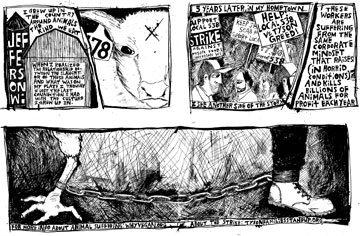

Tell us about the Animals and Workers art installation.

I was again attempting to put the viewer into a different position. It confuses

the perspective between the viewer, worker and animal on a factory farm. This

time the viewer almost trades places with the animal that would be heading down

this corridor on the way to slaughter. The corridor is much like a maze—you

don’t know what’s happening around the corner. This is actually done

in factory farms, to keep the animals from seeing others being killed. On the

last corridor of the installation, there are 400 ear tags hanging that the viewer

must pass in order to exit. At this point if someone wants to back out, they

can’t because other viewers are directly behind them. When you turn that

last corner you see a sign that reads, “There are 400 cows killed on the

average disassembly line in an hour.”

By the time they have exited the installation they come to the realization that

they have taken the same path—at least theoretically.

Now in zine #4, along with some of your more personal drawings, you illustrate

the Tyson Foods workers’ strike in your hometown of Jefferson. Tell us

about your involvement with it.

A lot of times my approach to art work is based on something I know and feel

strongly about. Having the strike so close to home, it was just something I needed

to address—to experience.

I was amazed that there were so many positive aspects. A town uniting for the

workers and against corporate greed leads to a real intense period of awareness

and rethinking of the actual position of these workers. As for my involvement,

I went down to support the striking workers with art that depicted them and their

concerns. That work got a lot of press in the local papers—in fact, the

papers were filled with coverage supporting the workers.

Was there any conflict of interest with supporting these factory workers, being

that you are vegan?

I’m interested in making connections. In a guttural sense I’m closest

to animal rights stuff, but so many different connections can be made from there.

It just makes more sense to try and connect with other people. To try and have

ideas that encompass more than one specific issue.

I think we make things too complicated. There are ways to support people and

animals. I mean, the best way to help someone is to ask and get a clear idea

of both their situation and needs. Know what’s going on in your town and

seek out a diversity of voices, not just the ones you tend to agree with.

I don’t consider what I’m doing with my art shows or zines to be

this sophisticated approach to anything. It’s just wanting to try and figure

out how to create some kind of honest representation of the world.

Are there any current projects you want to mention?

I’m currently working on a distorted narrative between a factory farm animal,

a factory farm worker, and a head boss. I’m doing individual stories of

each and then show where their lives cross paths. It’s an attempt to think

about the conditions we’re born into in this life and how that affects

who we are.

Roshni Koshy is a longtime vegan who lives on Staten Island. To learn more

about

Colin Matthes’ art or to order copies of the Ideas in Pictures zines,

visit www.ideasinpictures.org.

|

|

|

|