May

2004

Comfortable

Ignorance

By Rachel Cernansky

|

| December

2002/

January 2003 |

| |

Out of sight, out of mind. It’s a cliché

expression, but serves to represent the fundamental truth about the

state that our world, our humanity, is in.

So much of the western lifestyle thrives on the ability to distance

oneself from the realities that exist outside of the bubble that is

the western world. Our vast waste stream doesn’t bother us because

we don’t have to see or think about it when we’re through

creating it. Our relationship with food is so disconnected from the

global consequences of our choices and from the lives—both human

and non—that suffered because of it. The human exploitation in

sweatshop-made clothes is easily put out of mind by consumers who are

often fully aware of its existence, but would rather not think about

their personal contribution toward it.

I believe—or would like to—that people would live differently

if they were to come face to face with the misery they ultimately help

to promote. The power of choice is one of the profound differences between

the worlds of the north and south. While those in the north have the

option of whether or not to even think about the suffering woven into

one’s clothes, millions of workers chained to their workstations

do not have the power to choose when to urinate. They cannot live in

denial of other people’s suffering with the excuse that they had

a long day and deserve to relax, or with the justification that people

always have a choice, and could escape if they so desired. Their only

achievable escape is into a state of mental and physical numbness.

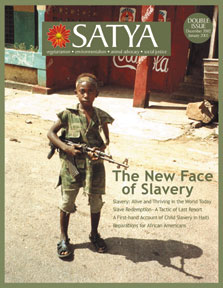

Human slavery is perhaps the epitome of this habit of denial. For those

of us who have never experienced or even witnessed it, slavery is something

so far out of our consciousness we can’t begin to imagine what

it’s like, nor can we comprehend how deeply it penetrates the

very existence of its victims. The physical torture is an obvious injustice,

a visible aspect we can relate to on some level. But the coping strategies

to which one must resort, if only subconsciously, to endure the trauma,

are utterly immeasurable. The impaired moral development of a 12 year-old

child soldier in Burma having to regularly beat his peers with a stick,

for instance, lest his own beating will follow—such lasting consequences

are at best underestimated by the outside world that can’t confront

the mere existence of slavery.

Slavery is invisible, and that’s what’s so cruel. Without

having to think about the misery involved, we have all kinds of goods

that better our lives. Anti-globalization activists are often criticized

for their naïve outlook, for not seeing the advantages that globalization

most certainly does provide. But such critics overlook the impact that

the globalized economy has had on the growing numbers who haven’t

benefited from it.

To say that life’s “just not fair,” that the current

global situation is “inevitable,” scapegoats the reality

that the north exploits entire peoples for a life of comfort and convenience.

We are cheating in a game that we won’t even admit was begun with

a headstart. The society we call the developed world was founded on

the backs of people kidnapped from their native lands, propelling us

into immense prosperity, prosperity we still enjoy the benefits of today.

Slavery may have changed hands since the days of the business it used

to be, and play by different rules. But the fact is, slavery still exists

and at its core, the means by which it does and its ultimate purpose

remain the same. Maybe we really haven’t advanced since that dark

moment in human “history” that we thought was behind us.

This power dynamic rings similar to that between man and factory farmed

animals. Today the ritual hunt is a trip to the grocer to pick up “what’s

for dinner,” a piece of meat de-boned and pre-trimmed to avoid

the messy reminders of what it once was. There is a similar hidden suffering

in most all the products that touch our lives, many of them pure luxury

items, yet we don’t think of them this way; we barely think of

them at all, which is perhaps the problem.

You’d never suspect the blood shed or limbs lost in mining the

diamonds we call the most precious of stones. Eating chocolate, you

don’t taste the human flesh that was sacrificed in growing and

harvesting the cocoa beans that make it so rich. And the disconnect

occurs on both ends—those who suffered could never dream of what

it’s like to taste what we ironically call a sinful indulgence

(worrying about excess calories, not about the guilt of exploitation).

Perhaps it would be comforting to know that this human misery went only

into luxury items. But it’s everywhere; it’s in the most

basic, mundane stuff we take for granted. Things like locks, bricks,

matches. And beedi cigarettes: hand-rolled cigarettes made in India

that involve such detail-intensive labor that the child’s fingers

suffer a lifetime from the minute movement and repetition—rolling

up to 2,000 per day; and their necks suffer from so much time spent

looking down at their work, with a matchbox propping up the chin, for

maximum concentration. That slave labor is producing things we don’t

even deem valuable seems to make a statement of how little we value

life itself. From a standpoint of born privilege, it is easy for people

to ignore and be complacent with the suffering they do not have to know.

But to value one human life over another; that is a decision no one

should be able to get away with so easily.

The existence of slavery is so pervasive it cannot be avoided; yet it

is physically impossible to pinpoint where and how it plays into our

lives. Whatever personal boycotts I have on animal products, on companies

exposed for sweatshop labor and so on, they do not help the 27 million

slaves living—barely—in the world today. As someone who

has chosen a vegan lifestyle for the compassion that I believe exists

within, and is deserved by, every living individual, this is a grappling

realization. It’s difficult enough to cope with the knowledge

of the misery that surrounds us. To know, however, that one can’t

avoid living, however consciously, at the expense of another individual’s

well-being—this is an entirely new struggle, and one we need to

face.

Rachel Cernansky is Assistant Editor of Satya.

This editorial was originally published in the special double issue

on Slavery (December 2002/January 2003).

|

|

|

|